If you’ve followed my blog for longer than 35 seconds, you’re keenly aware that our dogs are a huge part of my life. We have three: one is a mini goldendoodle - we call her “the baby,” which earns us giant eye-rolls from our other two, who are nine-year-old chocolate Lab mixes that we rescued from the shelter when they were just about eight weeks old.

One of those rescues, Lilly - who was at one time shy and nervous, and who would quiver when held, and hide under furniture if you walked straight toward her - is today a registered therapy dog.

A sweet and confident girl who takes on the stress and fear of others and melts it away like butter off the top of a dinner roll.

People often ask me what prompted me to go through therapy dog training with my dog, and it basically came from my freakish obsession with dogs. I knew from a young age that I wanted to work with them in some way.

I read online about eight or nine years ago about therapy dogs, and that sounded like something I wanted to try to do with my dogs someday.

In case you aren’t quite sure what a therapy dog is, and how it’s different from a service dog or an emotional support dog, here’s the main difference: a service dog and an emotional support dog work as a team with their handler to provide support for that handler.

A therapy dog works as a team with their handler to provide support for other people - people who are not their handler.

So in a nutshell, a service dog and emotional support dog provide comfort/aid/what-have-you for one person.

Lilly celebrating her birthday with the kids at Block House Creek Elementary School

A therapy dog provides those things for all different people.

There are lots of other differences, too, most of which are based on specific jobs a service dog is needed for, and legal designations and liberties, for which therapy dogs do not qualify.

Several years ago, after my dogs had grown out of the annoying puppy stage, I decided I’d work with them and get them trained enough with basic good-doggy manners, as the first step toward getting them into a therapy dog training program.

I worried about some of the skills I’d read would be required, especially having your dog sit and stay, then walking - with your back turned to them - about 10 feet away, with them continuing to stay, like some sort of magical unicorn dogs.

No. Way. would either of my dogs be able to pull that off.

Three or four years ago, I felt like I had them trained well enough, manners-wise, to get them into therapy dog training, where I’d (hopefully) learn to train those hard things.

The very first class was more of a screening, where the instructor gave us a brief 101 about therapy dogs versus service and emotional support dogs - just like I gave you at the beginning of this post - and then she went around to each dog to test out their temperament.

When she came around to Lilly, she sort-of patted all over her in a clumsy manner and got in her face, and Lilly leaned up against her, almost knocking her down (I was mortified! How can she be a therapy dog if she’s going to knock over little people?)

You could see in Lilly’s face that she was happy as a clam, her giant brown eyes half-closed and her tongue hanging out the side of her lazy grin.

Then the instructor came and did the same with Cooper.

My sweet boy stood stiff as a poker while she rubbed him down and hugged on him.

“Nope. This isn’t his thing,” she said to me.

My big, sweet, goofy boy is just too neurotic for therapy work.

Um, excuse me? Did she just nix Mommy’s Bestest Boyee?

She said he wouldn’t be able to move forward with the course, because he was showing stress and fear, and I’m like, um, you would, too, if you were manhandled in a room full of strangers, without even ONCE asking who’s the best boy.

I couldn’t even believe it, because Cooper is such a sweet boy, and I know he’d never hurt anyone. I didn’t understand how this precious boy of mine wasn’t passing the screening.

She did it again so she could point out his response: his tail tucked under and his eyes went wide and got all dilated, just like he does when I have to rub his rectum with that ointment to soothe his anal glands when they get all festered.

He felt violated.

The instructor explained to me that he likely felt he needed to protect me from her, and that is not the type of temperament suitable for a therapy dog, because if he’s afraid, that fear is likely to escalate to aggression.

She explained that 99% of what qualifies a dog for therapy work is his temperament.

“The behavior stuff can be trained,” she told me, “but you can’t train temperament.”

All the years I was prepping my dogs for those hard tasks, like sitting-and-staying, I never realized that that’s not even the part I should have been concerned with.

If you are interested in therapy work with your dog and you’re worried he doesn’t have what it takes because he digs or chews or acts a damn fool, you’re worrying about all the wrong things.

What your dog needs is a sweet, friendly, and confident temperament.

Like my Lilly, who ended up going through all the training and testing with flying colors, and the two of us are a registered therapy team with a complex rating, which means we can volunteer in situations that are a little more chaotic than, say, a library. Places like airports and courts, and things like that.

She even has her own Facebook page, but let’s keep that between us because Coop doesn’t know that part, yet, and I’d like to keep it that way for as long as possible.

Me and my girl, Lilly, in the Texas bluebonnets

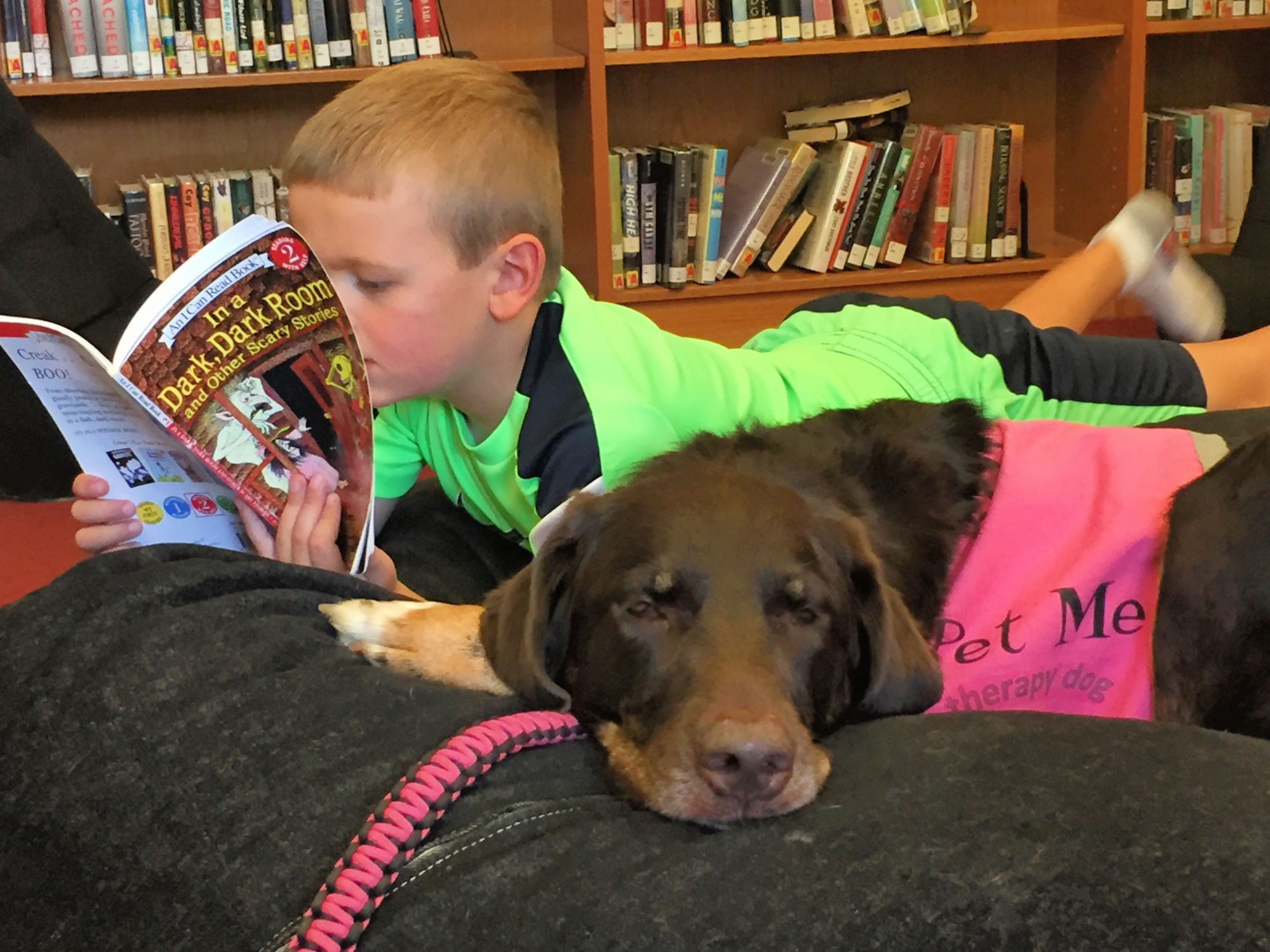

Lilly on the job at the Leander Public Library

I created a quiz for you to check and see if you and your dog have what it takes for therapy work.

If you think that you and your dog have what’s needed to be a therapy team, I can’t encourage it enough. It’s the most fulfilling work I’ve ever done, and there’s such a great need for more teams.

If you’re even a baby amount interested, look into local therapy dog trainings in your area. If you’re in Central Texas, I highly recommend The Dog Alliance in Leander. If you have any questions or comments, leave them below and I’ll get right back to you!